Many of you entering your 50s, 60s, and beyond can maintain independence and vitality by shifting how you train. You’ll get practical plans for strength, balance, mobility, and aerobic work, guidance on recovery and progression, and clear red flags for when to scale back to reduce fall risk or avoid overuse injuries, so you can safely build resilience and better mobility for long-term health.

Key Takeaways:

- Prioritize resistance training 2-3 times weekly to preserve muscle mass, bone density, and metabolic health; use progressive overload and compound movements scaled to ability.

- Combine low-impact aerobic exercise (walking, cycling, swimming) with balance and mobility work to support cardiovascular fitness, joint function, and fall prevention.

- Progress gradually and individualize plans-monitor intensity, allow adequate recovery, address pain or limitations, and consult healthcare or a qualified trainer as needed.

Understanding Longevity

As you move through your 50s and 60s, expect roughly 1% muscle loss per year without resistance work, rising risks for frailty and metabolic slowdown; preserving muscle and aerobic capacity cuts disability and hospital stays. Population studies link regular activity to lower all-cause mortality and maintained independence into the 70s and 80s. The WHO recommends 150-300 minutes of moderate aerobic activity weekly plus muscle-strengthening sessions two or more days per week.

- exercise

- longevity

- strength training

- cardio

- mobility

- nutrition

- sleep

- social connection

- genetics

The Importance of Exercise

You should prioritize progressive strength training and targeted aerobic work because resistance sessions twice weekly can increase strength by about 20-30% in older adults within three months, improve bone density, and lower fall risk when combined with balance drills; interval or sustained aerobic work raises VO2 max and metabolic health. Programs that mix compound lifts, gait practice, and mobility drills deliver functional gains. The best outcomes come from combining resistance, cardio, balance, and flexibility into a consistent routine.

- strength training

- aerobic

- balance

- flexibility

Factors That Affect Longevity

Your lifespan is shaped by both fixed and modifiable elements: genetics provide a baseline, while lifestyle-activity, diet, sleep, smoking, and chronic disease management-drives most risk. Social determinants like income, neighborhood walkability, and access to healthcare influence prevention and recovery after illness. Medication side effects and environmental hazards also matter. The interaction between these factors requires you to tailor training and recovery to medical history and living conditions.

- genetics

- lifestyle

- chronic disease

- nutrition

- sleep

- stress

- social support

- environment

For example, if you have type 2 diabetes, adding resistance training can lower HbA1c by roughly 0.3-0.6% over months and improve insulin sensitivity; smoking markedly increases cardiovascular risk while social isolation raises mortality risk by about 30% in meta-analyses. You should assess medications that impair balance or endurance and prioritize interventions with measurable outcomes. The most impact comes from addressing modifiable risks with targeted exercise, better sleep, and improved nutrition.

- diabetes

- smoking

- social isolation

- medication effects

- physical activity

- dietary quality

How to Start Exercising in Your 50s

Start with a brief self-assessment and, if you have medical issues, a quick check with your clinician. Aim for 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity per week, add 2 resistance sessions targeting major muscle groups, and do daily balance/flexibility work. Begin with 10-20 minute walks or cycling sessions, introduce one compound strength movement per workout, and raise volume by about 5-10% weekly. Watch for sharp joint pain and modify accordingly.

Choosing the Right Activities

Favor low-impact aerobic options like brisk walking, cycling, or swimming to protect joints; include resistance training using machines, bands, or bodyweight to combat muscle loss, and practice balance with single-leg stands or tai chi. For example, start with 15-minute walks three times weekly and two 20-minute band sessions focusing on 8-12 reps. Balance-focused programs can reduce fall risk by about 20-30%, while resistance work helps preserve bone density and mobility.

Setting Realistic Goals

Frame goals around daily function-carry groceries, climb stairs, or play with grandchildren-and make them SMART: specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound. Expect noticeable strength gains in 6-12 weeks with consistent resistance work and measurable endurance improvement within a month. Track simple metrics like minutes walked, sets/reps, and RPE, and set incremental targets (add 5-10% load or 5 minutes cardio each week).

Practical 12-week example: Weeks 1-4 do 3×/week 20-minute walks plus 2×/week resistance (2 sets of 8-12 reps with bands). Weeks 5-12 progress to 30-40 minute aerobic sessions and 3 sets, increasing load ~5-10% every 1-2 weeks as tolerated. Use metrics-step count, weight lifted, time to rise from a chair-and prioritize progressive overload. Stop and consult if you experience sharp joint pain or chest symptoms.

Exercise Tips for Your 60s

- Strength training

- Balance work

- Flexibility

- Aerobic activity

- Recovery and sleep

Aim for 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity weekly plus at least two strength sessions; include 10-15 minutes of daily flexibility and 3 balance sessions per week. Use compound moves, progressive overload of about 5-10% increases when pain-free, and monitor medication effects on exertion. Prioritize mobility to protect joints and preserve muscle mass, because reduced strength raises fall risk. Any plan you follow should be adjusted if you have joint pain, heart disease, or osteoporosis.

Strength Training Recommendations

Perform full-body strength sessions 2-3 times weekly, doing 2-3 sets of 8-12 reps for major lifts-squats (or chair squats), rows, hip hinges, and modified push-ups; start with resistance bands or machines if balance or technique limits you. Progress by adding 5-10% load or 1-2 reps every 2-4 weeks, rest 48 hours between sessions, and emphasize proper form to lower injury risk; if you’ve had fractures, focus on controlled eccentric work under professional guidance.

Incorporating Flexibility and Balance

Include 10-15 minutes of dynamic warm-ups before exercise and 10-15 minutes of static stretching after, holding each stretch 20-30 seconds; add balance drills (single-leg stands up to 30 seconds, tandem walking, heel-to-toe) for 10-15 minutes, three times weekly. Integrate Tai Chi or yoga classes shown to improve proprioception, and prioritize ankle and hip mobility to reduce fall risk.

Progress balance by reducing base of support or adding dual tasks (turning your head while standing) and use a chair or partner for safety when needed; perform ankle-strengthening (calf raises, resisted dorsiflexion) and proprioceptive exercises on foam pads as tolerance grows. Remove home trip hazards, wear supportive footwear during practice, and track improvement (timed single-leg hold, gait speed) to guide progression and keep you safe while gaining function.

Staying Active in Your 70s and Beyond

Aim for a mix of aerobic, strength and balance work: target 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity weekly in manageable sessions, plus strength training at least twice weekly and daily balance practice. Choose low-impact options like water aerobics, brisk walking, tai chi or chair-based resistance if you have joint issues, and prioritize fall prevention through ankle-focused exercises and regular vision and medication reviews. Track progress with a step counter or a 6-minute walk test every 3 months to adjust intensity safely.

Adapting Your Routine

Scale intensity using Rate of Perceived Exertion (aim ~3-5/10 for steady work and 6-7/10 for short intervals); favor 10-15 minute daily mobility and balance sessions plus two 20-30 minute resistance workouts weekly using bands or machines (2 sets of 8-12 reps). Substitute low-impact options like cycling or water workouts for running, use seated progressions when needed, and monitor blood pressure; if you have arrhythmia or uncontrolled hypertension, consult your clinician before heavier loads to reduce fracture and joint injury risk.

Social and Mental Benefits of Exercise

Group activity boosts adherence and mood: meta-analyses link regular physical activity with up to a 30% lower risk of cognitive decline and show exercise reduces depressive symptoms by roughly 20-30% in older adults. Joining walking groups, senior-center classes or dance sessions gives daily social contact and structured routines, which both improve consistency-look for programs with small class sizes and trained instructors to maximize safety and benefit.

Randomized trials of 12-24 week group programs-dance, aerobic classes or tai chi-demonstrate measurable gains in executive function and memory, while tai chi studies report ~30-45% fewer falls over 6-12 months. You’ll get the biggest payoff by attending classes 2-3 times weekly and adding two short home sessions; if transport is a barrier, try virtual group classes or a buddy system through local community centers to preserve both social connection and the cognitive benefits.

How to Maintain Motivation

Set clear, measurable targets and build them into your week so you hit the CDC guideline of 150 minutes of moderate activity plus two strength sessions. Vary workouts-walking, resistance, balance-to keep interest and reduce injury risk. Use calendar blocks, short habit-stacking (e.g., 10 minutes after breakfast), and a simple reward system for streaks. If you feel chest pain, sudden dizziness, or breathlessness, stop and seek medical attention; otherwise, small, consistent steps beat sporadic intensity for long-term gains.

Finding Your Community

Join local groups like SilverSneakers classes, a Masters swim lane, or a neighborhood walking meetup that meets 3 times per week to create accountability and social support. Partner with a training buddy for twice-weekly strength sessions, or plug into online forums and Facebook groups where members share weekly logs and tips. When you train with peers who match your pace and goals, adherence and enjoyment both increase, making it easier to keep showing up.

Tracking Your Progress

Log workouts with metrics you can improve: minutes, sets/reps, load, step count, resting heart rate, and BP readings. Use simple tools-paper log, Strava, or a fitness watch-and aim for measurable, incremental gains like increasing weight or reps by 5-10% every 4-8 weeks. Focus on consistency metrics (sessions per month) as much as performance; small, steady improvements predict long-term success.

Start with baseline tests-6-minute walk distance, 30-second chair-stand, and a grip-strength reading-to track function. Keep a weekly summary: total minutes, strength volume (sets × reps × load), RPE, sleep, and meds. Review monthly trends and adjust load by about 5-10% when you hit consistent gains for 4-8 weeks. Include objective health checks like BP and fasting glucose; if BP exceeds 160/100 mmHg or you have new cardiorespiratory symptoms, pause intensity and consult your clinician before progressing.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

You’ll slow progress when you stick to one mode, ignore mobility, or skip strength and balance work; after 50 you can lose about 1% muscle mass per year if you don’t resist-train. Programs that copy younger athletes, ignore progressive overload, or undervalue recovery raise your risk of falls, tendon injury, and chronic fatigue. Aim for varied sessions, targeted hip and ankle mobility, and a plan that builds intensity by small, measurable steps over weeks.

Overtraining Risks

Pushing high-intensity work too often causes persistent soreness, sleep disruption, and immune suppression; you often need 48-72 hours to recover from a truly intense strength or interval session. Limit maximal efforts to about 2-3 sessions per week, monitor resting heart rate and perceived exertion, and back off if performance or mood declines. Tendinopathy and stress fractures commonly follow sustained overload without adequate recovery.

Ignoring Body Signals

If you dismiss sharp pain, persistent swelling, numbness, or chest discomfort you risk worsening injury; mild muscle soreness is normal, but sharp joint pain, new instability, or tingling are red flags. Stop or modify the exercise, reduce load or range, and track symptoms – continuing through dangerous pain increases recovery time and can lead to chronic problems.

You can use concrete thresholds to guide action: treat soreness as 0-3/10, scale back if pain reaches 4/10 or higher, and pause for swelling, locking, or neurological signs. Rest, ice, and a short taper often help within 72 hours; if symptoms persist or worsen, get a targeted assessment (physio, sports medicine) and adapt your program with alternative movements that preserve fitness while protecting the injured tissue.

To wrap up

To wrap up, prioritize strength training to maintain muscle and bone, practice balance and mobility daily, include aerobic work for heart health, progress gradually to challenge your body, allow adequate recovery, tailor workouts to your goals and limitations, work with qualified professionals when needed, and make consistent movement part of your lifestyle to preserve independence and vitality into your 50s, 60s, and beyond.

FAQ

Q: What types of exercise should people in their 50s, 60s, and beyond prioritize for long-term health?

A: Prioritize four pillars: resistance training to preserve and build muscle and bone (full-body sessions 2-3 times per week, 2-4 sets of 6-12 reps for strength, 8-15 for endurance); aerobic activity for cardiovascular health (accumulate 150 minutes/week moderate intensity or 75 minutes/week vigorous, or a mix); balance and gait practice to reduce fall risk (short sessions 3-7 days/week – single-leg stands, tandem walking, heel-to-toe, or progressive challenges); and mobility/flexibility work (dynamic warm-ups before activity, static stretching or foam rolling after). Include occasional power-style work (light load, faster concentric movement) 1-2 times/week to maintain speed and function. Use joint-friendly options (walking, cycling, rowing, water exercise) if needed, and aim for exercises that mimic daily tasks (sit-to-stand, step-ups, carrying) to preserve independence.

Q: How often and how hard should workouts be, and how do I progress safely with age?

A: Start with a baseline you can complete consistently and increase gradually. Resistance: 2-3 sessions/week; cardio: most days of the week totaling recommended minutes; balance and mobility: short daily or near-daily practice. Use effort scales (RPE 5-7 of 10 for moderate work, 7-8 for harder sets) and prioritize good technique over heavy weight. Progress by increasing volume or load about 5-10% per week, adding a set or a small weight increment, or increasing time/intensity of aerobic sessions by similar small steps. Schedule at least one full rest day per week and easier recovery sessions after harder workouts. If new to exercise or returning after illness/surgery, begin with lower frequency and shorter sessions (10-20 minutes) and build over 6-12 weeks. Seek professional guidance for individualized progression if you have multiple health issues.

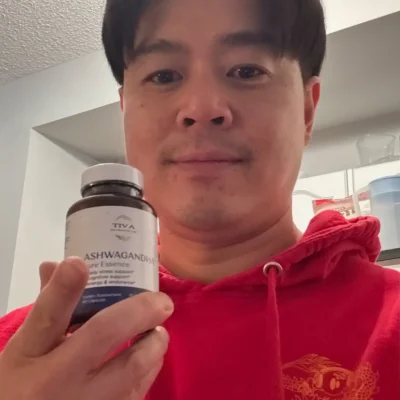

Q: How should I manage joint pain, chronic conditions, recovery, and nutrition to support long-term training?

A: For joint pain use low-impact modalities (swimming, cycling, elliptical), focus on strengthening muscles around the joint, and reduce painful ranges while maintaining overall activity. For chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, heart disease), get medical clearance as needed, tailor intensity and exercise type to symptom control, and coordinate with your clinician about medication effects (e.g., blood pressure, glucose responses). Prioritize recovery: adequate sleep (generally 7-9 hours), regular rest days, and active recovery sessions. Nutrition: consume sufficient protein (many older adults benefit from roughly 1.0-1.6 g/kg/day depending on activity and kidney health) spread across meals with 20-40 g per meal to support muscle repair, ensure adequate calories, and maintain bone-supporting nutrients (calcium, vitamin D) as advised by your provider. Stop exercise and seek immediate care for warning signs such as chest pain, sudden severe breathlessness, fainting, severe dizziness, new neurologic deficits, or rapidly worsening joint swelling; consult a physical therapist for persistent pain or functional decline to get a tailored plan.